If diplomats have groundhog days, when they are condemned to reliving the same 24 hours, perhaps Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, felt a certain weariness as his jet approached the Middle East on his latest trip.

It is his eighth diplomatic tour of the region in the eight months since the Hamas attacks on Israel on 7 October last year.

The politics of trying to negotiate an end to the war in Gaza and an exchange of Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners were already complicated.

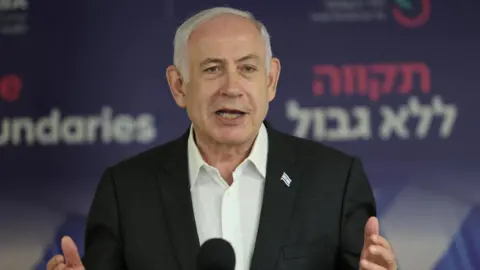

They are more tangled than ever now that the Israeli opposition leader Benny Gantz has resigned from the war cabinet of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, along with his political ally Gadi Eisenkot. Both men are retired generals who led the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) as chiefs of staff.

Without Benny Gantz, the Americans have lost their favourite contact in the cabinet. Now he’s back in opposition, Mr Gantz wants new elections – he is the pollsters’ favourite to be the next prime minister – but Mr Netanyahu is safe as long as he can preserve the coalition that gives him 64 votes in the 120-member Israeli parliament.

That depends on keeping the support of the leaders of two ultranationalist factions. They are Itamar Ben-Gvir, the national security minister, and Bezalel Smotrich, the finance minister.

That is the point at which Secretary of State Blinken’s mission collides with Israeli politics. President Joe Biden believes that the time has come to end the war in Gaza.

Mr Blinken’s job is to try to make that happen. But Messrs Ben-Gvir and Smotrich have threatened to bring down the Netanyahu government if he agrees to any ceasefire until they are satisfied that Hamas has been eliminated.

They are extreme Jewish nationalists, who want the war to continue until no trace of Hamas remains.

They believe that Gaza, like all the territory between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan, is Jewish land that should be settled by Jews. Palestinians, they argue, could be encouraged to leave Gaza “voluntarily”.

Antony Blinken is in the Middle East to try to stop the latest ceasefire plan from going the way of all the others. Three ceasefire resolutions in the UN Security Council were vetoed by the US, but now Joe Biden is ready for a deal.

On 31 May, the president made a speech urging Hamas to accept what he said was a new Israeli proposal to end the war in Gaza.

It was a three-part deal – which has now been backed by a UN resolution – starting with a six-week ceasefire, a “surge” of humanitarian aid into Gaza, and the exchange of some Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners.

The deal would progress to the release of all the hostages, a permanent “cessation of hostilities” and ultimately the huge job of rebuilding Gaza. Israelis should no longer fear Hamas, he said, because it was no longer able to repeat 7 October.

President Biden and his advisers knew there was trouble ahead. Hamas insists it will only agree to a ceasefire that guarantees an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza and an end to the war.

The destruction and civilian death inflicted by Israel in Nuseirat refugee camp in Gaza during the raid to free four hostages last week can only have strengthened that resolve. The Hamas-run health authorities in Gaza say that 274 Palestinians were killed during the raid. The IDF says the number was less than 100.

Mr Biden also recognised that some powerful forces in Israel would object.

“I’ve urged the leadership in Israel to stand behind this deal,” he said in the speech. “Regardless of whatever pressure comes.”

The pressure came quickly, from Messrs Ben Gvir and Smotrich. They are senior government ministers, viscerally opposed to the deal that Joe Biden presented. It made no difference to them that the deal was approved by the war cabinet, as they are not members.

As expected, they threatened to topple the Netanyahu coalition if he agreed to the deal.

Neither Hamas nor Israel have publicly committed to the deal that President Biden laid out.

He accepted that the language of parts of it needed to be finalised. The ambiguity in parts of the proposal might in other conflicts, between other belligerents, allow room for diplomatic manoeuvre. But that would require a shared realisation that the time had come to make a deal, that more war would not bring any benefit.

There is no sign that the Hamas leader in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, is at that point. He seems determined to stick the course he has followed since 7 October.

Some reports out of Gaza said that Palestinians in the ruins of Nuseirat camp were swearing at Hamas as well as Israel for disregarding their lives.

The BBC cannot confirm that, as like other international news organisations it is not allowed by Israel and Egypt to enter Gaza, except under rare and highly supervised trips with the Israeli military.

It seems clear though, that vast numbers of Palestinian dead have strengthened, not weakened the resilience of Hamas. For them, survival of their group and its leaders equals victory.

They will focus on the fact that the killing of more than 37,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians – according to the health ministry in Gaza – have brought Israel into deep disrepute.

It faces a case alleging genocide at the International Court of Justice, and applications at the International Criminal Court for arrest warrants for Benjamin Netanyahu and Israel’s Defence Minister Yoav Gallant.

On the Israeli side, Prime Minister Netanyahu has lost two members of the war cabinet, Messrs Gantz and Eisenkot, who wanted a pause in the war to allow negotiations to free hostages. He is more exposed, without the political insulation they provided, to the hardliners, Messrs Ben-Gvir and Smotrich.

Perhaps Antony Blinken will urge him to call their bluff, to make the deal and satisfy millions of Israelis who want the hostages back before more of them are killed.

Mr Netanyahu might then have no choice other than to risk his government by gambling on an election.

Defeat will bring forward commissions of enquiry that will examine whether he bears responsibility for the political, intelligence and military failures that allowed Hamas to break into Israel eight months ago.

Or Benjamin Netanyahu might default to the techniques of procrastination and propaganda that he has perfected over all his years as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister.

If in doubt, play for time, and push arguments harder than ever.

On 24 July, he will return to one of his favourite pulpits, when he addresses a joint session of the US Congress in Washington DC.