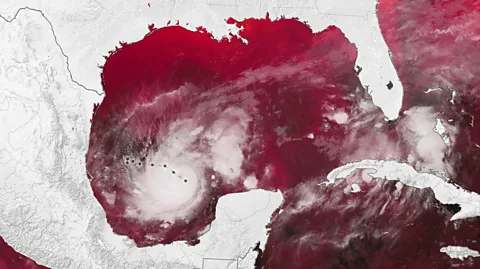

These images show where Hurricane Milton’s power came from, and some of the risks faced by those in its path.

Hurricane Milton is one of the most powerful storms to form over the Atlantic in recent years. The National Hurricane Center has warned that Milton will make landfall as an “extremely dangerous major hurricane” late on Wednesday night or early on Thursday morning. Packing powerful winds of up to 145mph (233km/h), Milton is expected to cause flash flooding, torrential rain and storm surges in Florida. Millions of residents are racing to evacuate as the category four storm barrels towards the state’s coastline.

Milton arrives less than two weeks after Hurricane Helene devastated the Gulf Coast and killed at least 225 people in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina.

Nasa Earth Observatory

Nasa Earth ObservatoryOn 5 October, Hurricane Milton began life as a tropical storm in the south west of the Gulf of Mexico. The next day, its wind speed started to rapidly intensify – and by 7 October it had reached category five strength. Milton’s winds had increased from 80 to 175mph (129 to 282 km/h) in just 24 hours. It is now one of the fastest intensifying Atlantic storms on record.

A hurricane forms when a weather disturbance, like a thunderstorm, pulls in warm surface air from all directions. Seawater evaporates and is dragged upwards by converging winds. As it rises, the water vapour cools and condenses into clouds and rain – and more warm moist air spirals up from the surface to replace it. And warmer oceans, mean more extreme hurricanes, experts warn.

Nasa Earth Observatory/ Michala Garrison

Nasa Earth Observatory/ Michala GarrisonHurricane Milton formed in the Gulf of Mexico at the same time that two other large hurricanes were churning above the Atlantic. Hurricane Leslie, in the bottom-right hand corner of the image above, and Hurricane Kirk, towards the top-right, formed a trio of storms on 6 October as Hurricane Milton was gaining strength.

It is unusual to see three storms forming at once this late in the season, meteorologist Philip Klotzbach of Colorado State University pointed out on X, formerly known as Twitter. In fact, it is the first time this number of hurricanes has been seen simultaneously across the Atlantic in the month of October since satellite records began in 1966.

“The ocean temperature in the Gulf of Mexico is at or near record levels right now and this provides hurricanes over that region with plenty of ‘fuel’,” says Joel Hirschi, associate head of marine systems modelling at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC).

The North Atlantic has been “running a fever” for the past year, and sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are currently well above average.

“A warmer climate means warmer seas,” says Hirschi. “There is growing evidence that the time needed for tropical cyclones to intensify to powerful category four or five storms is reducing as climate warms. The rapid intensifications we have seen in the Atlantic for Beryl, Helene and now Milton follow that pattern.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the powerful winds and gusts that Milton is expected to bring to Florida will be damaging, it is also creating conditions that are likely to see tornadoes develop across central and southern Florida, according to the National Weather Service. Flooding is also more likely as soil moisture levels in many parts of Florida remain following heavy rainfall brought by Helene, which means the ground is not able to absorb as much water.