The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has lost some of its power to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

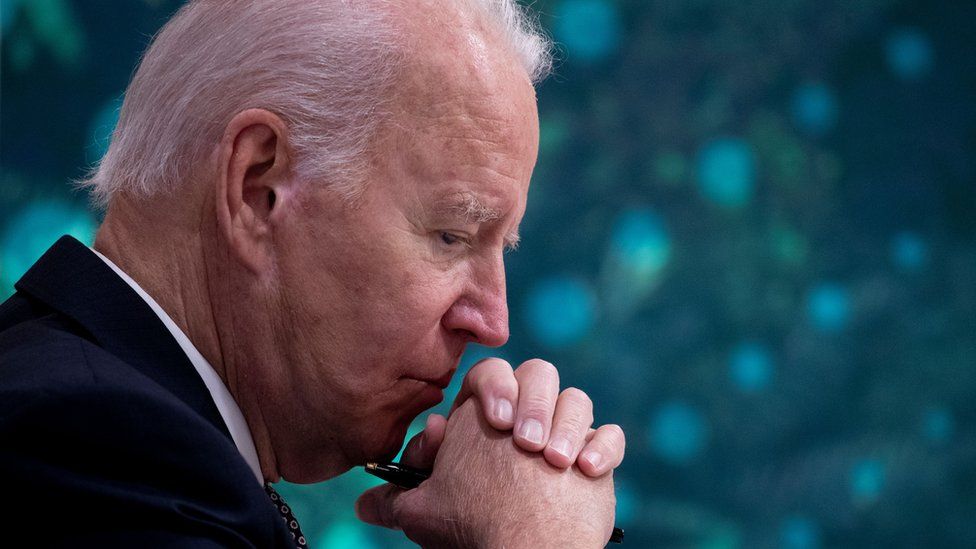

The landmark ruling by the US Supreme Court represents a major setback to President Joe Biden’s climate plans.

He called it a “devastating decision” but said it would not undermine his effort to tackle the climate crisis.

The case against the EPA was brought by West Virginia on behalf of 18 other mostly Republican-led states and some of the nation’s largest coal companies.

They argued that the agency did not have the authority to limit emissions across whole states.

These 19 states were worried their power sectors would be forced to move away from using coal, at a severe economic cost.

Attorney General Eric Schmitt for Missouri – one of the 19 states – called it a “big victory… that pushes back on the Biden EPA’s job-killing regulations”.

The court hasn’t completely prevented the EPA from making these regulations in the future – but says that Congress would have to clearly say it authorises this power. And Congress has previously rejected the EPA’s proposed carbon limiting programmes.

Environmental groups will be deeply concerned by the outcome as historically the 19 states that brought the case have made little progress on reducing their emissions – which is necessary to limit climate change.

The states made up 44% of the US emissions in 2018, and since 2000 have only achieved a 7% reduction in their emissions on average.

“Today’s Supreme Court ruling undermines EPA’s authority to protect people from climate pollution at a time when all evidence shows we must take action with great urgency,” said Vickie Patton, general counsel for Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

It means President Biden is now relying on a change of policy from these states or a change from Congress – otherwise the US is unlikely to achieve its climate targets.

This is a significant loss for the president who entered office on a pledge to ramp up US efforts on the environment and climate.

On his first day in office he re-entered the country into the Paris Agreement, the first legally-binding universal agreement on climate change targets.

And he committed the country to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 52% by 2030 against 2005 levels.

“While this decision risks damaging our nation’s ability to keep our air clean and combat climate change, I will not relent in using my lawful authorities to protect public health and tackle the climate crisis,” he said.

The outcome of this case will be noted by governments around the world, as it will affect global efforts to tackle climate change. The US accounts for nearly 14% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

A United Nations spokesman called it “a setback in our fight against climate change” but added that no single nation could derail the global effort.

In the US, this ruling could also affect the EPA’s broader existing and future regulatory responsibilities – including consumer protections, workplace safety and public health.

The ruling gives “enormous power” to the courts to target other regulations they don’t like, Hajin Kim, assistant professor of law at University of Chicago, tells the BBC.

This is because judges can say Congress did not explicitly authorise the agency to do that particular thing, she adds.

For decades, the Supreme Court has held that judges should generally defer to government agencies when interpreting federal law. On Thursday, the conservative majority continued a recent trend of chipping away at that practice.

Instead, the court’s justices embraced what’s called the “major questions doctrine” – which asserts that a federal agency’s discretion is limited on big issues that involve broad regulatory actions. If Congress had intended the Environmental Protection Agency to be able to issue sweeping regulations of an entire sector of the US economy, they said, it would have explicitly written that power into the Clean Air Act.

In January, a similar majority of the court cited the major questions doctrine to strike down an attempt by the Biden administration to use a federal workplace law to mandate vaccinations for employees in large companies.

It’s now clear this court will turn a sceptical eye to agency attempts to cite vague or broad laws to enact any sort of major regulatory changes. That’s a significant development, given how difficult it has been for Congress to pass substantive new legislation in recent years. The time when presidents could find unilateral “work-arounds” in existing law may be coming to an end.